![]()

ABBA weren’t forged in the fires of global ambition or preordained stardom—they were, in the most gloriously roundabout way possible, an outcome of Eurovision. Not just launched by it. Shaped by it. Practically constructed in its image.

The oft-overlooked origin point? Melodifestivalen 1969. Benny Andersson, one half of what would become ABBA’s songwriting engine, enters the Swedish national selection contest with “Hej clown.” He doesn’t win. Nobody remembers the song. But something far more significant happens: he meets fellow contestant Anni-Frid Lyngstad. She finished fourth. He didn’t even qualify for the big stage. But within a month they’re a couple. That’s the true victory.

In the same month, Björn Ulvaeus—still deep in the folky quagmire of the Hootenanny Singers—meets solo artist Agnetha Fältskog. Again, no global charts. No gold records. Just two people finding a weird little alignment in their careers and falling into each other’s creative orbit.

By 1970, the tangled romantic-professional web begins to form. Benny and Björn record the album Lycka. Agnetha and Frida provide backing vocals. Their voices, as yet unnamed as ABBA, melt beautifully together. The synergy is there. Nobody notices. Yet.

Then comes Ring Ring, their 1973 Eurovision bid. Surely the moment of triumph?

No. They don’t even win the national final. A group called “Malta”—no, not the country—does. The humiliation is mitigated only by the absurdity. The band, still called “Björn, Benny, Agnetha & Anni-Frid” (a branding catastrophe), comes third. Third. And yet, Ring Ring becomes a hit regardless. Commercial reward in the absence of institutional validation. Classic Eurovision.

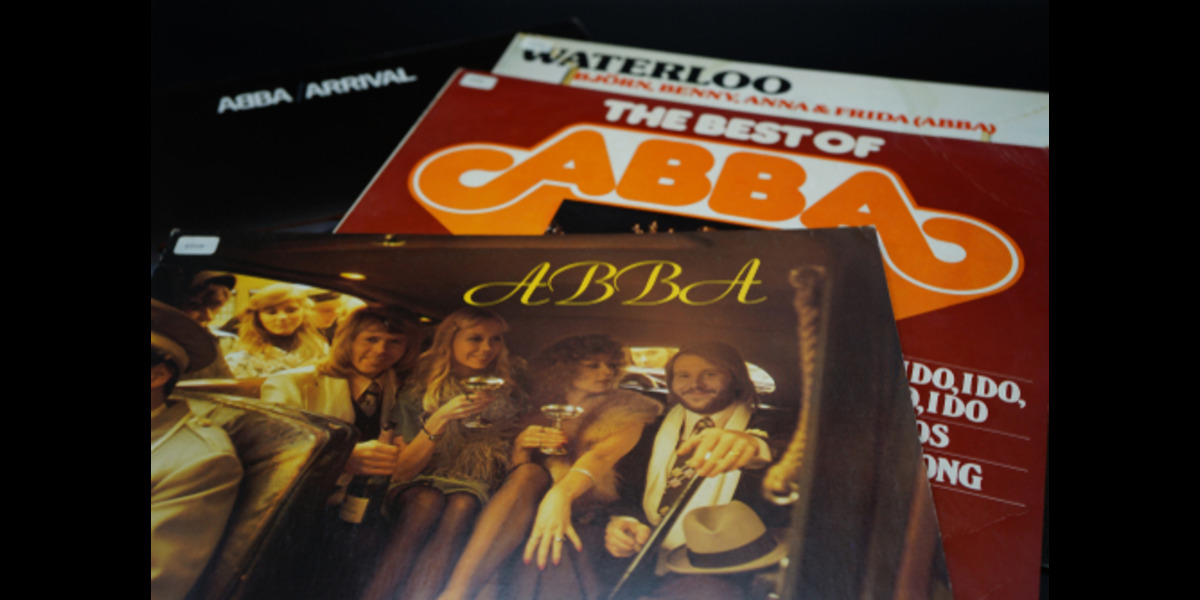

But they return, and in 1974, everything changes. “Waterloo” is a banger. That’s not up for debate. It wins Melodifestivalen with 302 points, obliterating the competition. Eurovision, held in Brighton, becomes the crucible. This time they perform as ABBA. No more ridiculous acronym spelling bees. They sing in English. They wear... those outfits. The UK gives them zero points—because of course it does—but they win anyway.

And suddenly, the world submits.

Waterloo rockets up the global charts. The win is seismic. Unlike most Eurovision victors who vanish back into obscurity within six weeks, ABBA use the platform as a trampoline. Not a stepping stone. A launchpad. This wasn’t the start of a nice run—it was the start of dominance.

Over the next decades, their Eurovision legacy is burnished through tributes, puppets (yes, really), and the persistent re-airing of that 1974 performance. Even in 2024, for the 50th anniversary of Waterloo, they make a virtual appearance via their ABBA-tars—because of course they do. Björn later explains: "We just thought we would be better represented by our avatars." That’s not distancing. That’s myth-making.

To this day, ABBA’s place in Eurovision lore is unshakeable. They didn’t just win it. They elevated it. In return, it gave them everything: love, collaboration, failure, fame.

Without Eurovision, there is no ABBA. No Dancing Queen. No Mamma Mia. No pop royalty.